Last Friday, a number of high profile sites were indirectly attacked by a huge flood of traffic to their DNS servers.

It appears that the source of the attack were millions of infected Web cameras, DVRs and other Internet-connected devices. (So it's a good idea to update the default passwords on those devices.)

But for people who run Websites, the more critical piece is just how the Websites were attacked.

The sites were not attacked directly. Instead, the domain name to IP translation system, known as DNS, was attacked with a flood of bogus requests.

What's DNS?

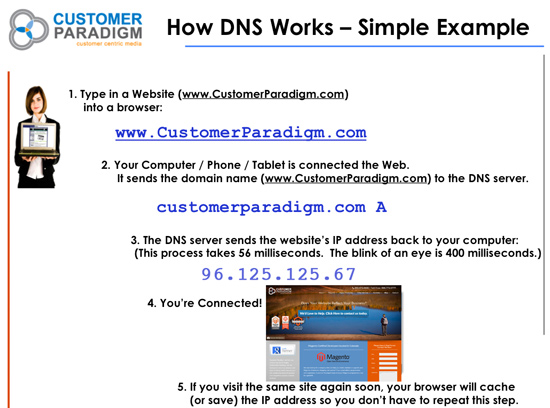

When an end user types in a domain name into a browser, such as www.CustomerParadigm.com, there is a set of servers that translate this domain name into an IP address - giving your computer, tablet or phone the exact address for your Website. In the case of Customer Paradigm, the translation is an A record that points to 96.126.125.67.

How this actually works:

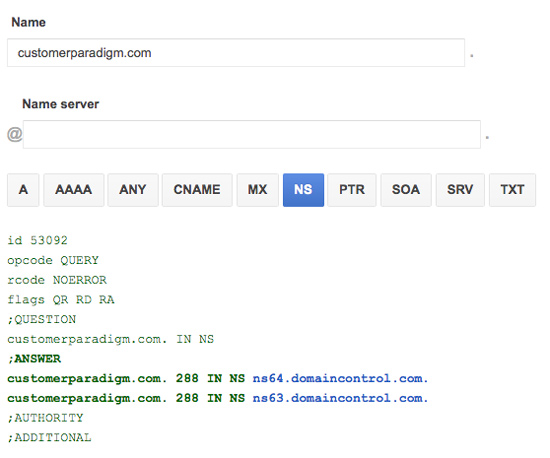

1. Domain Name Registration. When you register a domain name with a registrar, you are asked to specify at least two name servers for your domain. Most of the hosting companies now have free services available that allow you to manage your DNS zone file records through their system.

For Customer Paradigm, our two name servers are: ns63.domaincontrol.com and ns64.domaincontrol.com:

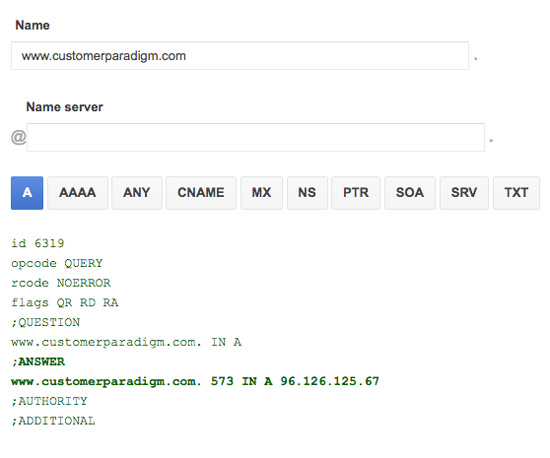

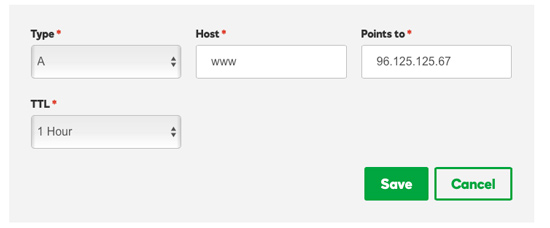

2. DNS Zone File. If I want to add a new server, (such as set up a site like http://Amazing.CustomerParadigm.com) or change where the www.CustomerParadigm.com server is located, I need to update the DNS zone file with the appropriate records.

Although there are a number of different records, the most common is an A record. An A record translates a domain name (i.e. www.CustomerParadigm.com) to an IP Address (i.e. 96.126.125.67):

When I make a change to a DNS record, it's saved on both of our name servers:

3. Domain to IP Translation Service. When you type in a domain name into a browser, or click on a link in an email, text message or on a web page that goes to a different domain, your computer reaches out in a series of steps to figure out where to go.

First, your device needs to find the name servers for the domain you want to visit.

Next, your device will contact the name servers to find out what IP address you should use to connect for your device.

Higher volume sites might have more than one Web server, so the IP address that is returned might go to a load balancer or multiple nodes that are geographically dispersed.

4. DNS Caching. It's not very efficient for your computer, tablet or mobile device to have to look up the IP address for sites you commonly visit. So in many cases, the A record for the DNS zone file (the IP address for the site) will be saved in your computer's memory. It's also possible that the DNS lookup will be saved in your computer's router, or even upstream at your router's DNS lookup system.

DNS zone file records have a Time to Live value (TTL) that specify how long they should be cached. For many sites, it can be set to several days or a week; if you're about to move to a new hosting provider, you should set the TTL low - perhaps 30 minutes.

More About the Attack:

Last Friday's attack flooded the DNS server's for many of the top sites (Twitter, Netflix, PayPal and others) with overwhelming traffic. There was so much traffic that normal requests simply couldn't get through.

It's a lot like rush hour traffic in a major city, when everyone is trying to leave at just the same time. The roads are fine, the cars on the roads are in perfect working order. The traffic lights, bridges and everything are working. But instead of 10,000 cars trying to leave at the same time (which slows things down), think what happens when you have ten million cars trying to move in the same place. Everything grinds to a halt.

The challenge with a DDOS (Distributed Denial of Service) attack is that it's tougher to pinpoint real traffic from fake traffic.

If it's just one or two servers trying to flood a server with traffic, it's easy to deny access to a single computer or small network. But because so many different devices were trying to connect with DNS lookups, this was a tougher thing to defend against.

What can you do?

First, make sure that you know where your domain is registered, and that you have access to the registration information. If you ever need to update your DNS, this is the first place you'll need to access to make any changes.

Second, make sure you know where your DNS is hosted. This might be at the same place as your domain registration, or possibly with your hosting company. If you have access to your DNS, you'll be able to change it if you need to.

Finally, make sure that your TTL (Time To Live) for your website is not set too high. If you need to make a quick change, a seven day TTL may be problematic for frequent visitors to your site.

I hope this helps... Let me know if you'd like me to review your DNS settings for you.

Thanks!

Jeff Finkelstein

Founder, Customer Paradigm

303.473.4400